Psychology in the Middle Ages

Part II

Part II

For the entire period spanning the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, until the first glimmerings of the Renaissance, the theology and doctrines of the Christian church held sway in most of Western Europe. The growth of Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy drove Paganism and other beliefs to the periphery, delineating between Christians and non-Christians in much the same way that Greeks looked down upon uncivilized barbarians.

This article is a part of the guide:

Browse Full Outline

- 1History of the Scientific Method

- 2Who Invented the Scientific Method?

- 3Before the Greeks

- 4Mesopotamia

- 5Greek Science

- 6Building Roman Roads

- 7Islamic Science

- 8Middle-Ages Science

Psychology in the Middle Ages (Part I)

Psychiatry and Christian Scholasticism

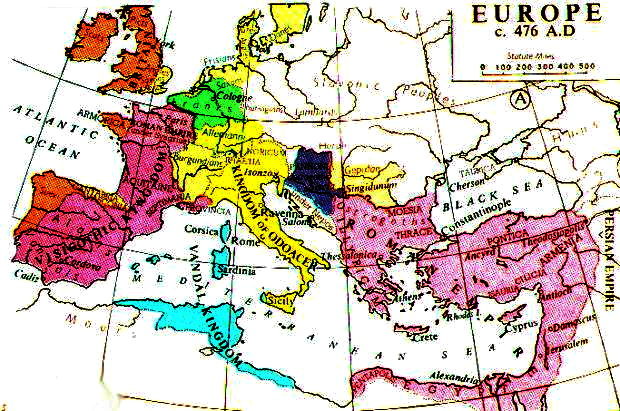

Although there is some disagreement about the extent of the Middle Ages, they are regarded as the period from the fall of the Roman Empire and the sacking of Rome by the Goths, in 467CE, to the capture of Constantinople by the Turks, in 1453. During this period, Europe went through a number of upheavals, socially, economically, and politically, as the stability brought by the Romans crumbled.

Although there is some disagreement about the extent of the Middle Ages, they are regarded as the period from the fall of the Roman Empire and the sacking of Rome by the Goths, in 467CE, to the capture of Constantinople by the Turks, in 1453. During this period, Europe went through a number of upheavals, socially, economically, and politically, as the stability brought by the Romans crumbled.

During this period of human history, the study of the physical world was largely guided by Christian doctrine, and scholars usually referred to biblical interpretations as the starting point for study. They built philosophical treatises around Christianity or, alternatively, were too afraid to challenge the status quo, lest they be branded as heretics and punished. In general, scientific study regressed markedly in Western Europe during this period.

The Psyche and Divinity

The study of the mind was slightly different, largely because thought and soul were inextricably linked. Psychology was described in theological terms, based upon the idea that thought and perception; the psyche, were part of religion and connection between deity and soul. The study of the mind was certainly not neglected during the Middle Ages. In fact, many theologians and scholars focused upon such studies as part of the quest to understand the link between humanity and divinity.

Largely, the Ancient Greeks concentrated upon abstraction and reasoning, with their impersonal, bickering gods perhaps a reflection of their society. By contrast, the Christian idea of the immortal soul led to a focus on the individual as the central figure. Because every person possessed an immortal soul, they were significant and worthy of ‘salvation.’

The Western European theologians drew upon the Judaic ideas of the nature of God, namely that God was the perfect creator, transcending the physical realm. Humans were the pinnacle of creation, and were regarded as higher than animals, capable of thought but also possessing a soul that linked every individual human to the divine. In Alexandria, these Judaic ideas fused with Greek philosophy and, from this fusion of cultures and philosophies, the Christian attitude to the philosophy of the mind and soul arose. This paradigm would shape the prevalent attitudes towards the mind for centuries.

The Western European theologians drew upon the Judaic ideas of the nature of God, namely that God was the perfect creator, transcending the physical realm. Humans were the pinnacle of creation, and were regarded as higher than animals, capable of thought but also possessing a soul that linked every individual human to the divine. In Alexandria, these Judaic ideas fused with Greek philosophy and, from this fusion of cultures and philosophies, the Christian attitude to the philosophy of the mind and soul arose. This paradigm would shape the prevalent attitudes towards the mind for centuries.

According to the new Christian beliefs, man had an inner spirit, the Πνεύμα, which was separate from the soul and the body, perhaps reflecting the beliefs of Christians in the tripartite nature of God. This encouraged a certain amount of introspection, but this was also tempered by the idea of Christian fellowship brought about by shared worship. This particular slant towards an inward-looking, introspective belief is more apparent in the modern Greek Orthodox Church, which still blends Christian theology with the philosophy of the Ancient Greeks and Oriental mysticism.

Martyn Shuttleworth (). Psychology in the Middle Ages. Retrieved Mar 01, 2026 from Explorable.com: https://explorable.com/middle-age-psychology-2

You Are Allowed To Copy The Text

The text in this article is licensed under the Creative Commons-License Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

This means you're free to copy, share and adapt any parts (or all) of the text in the article, as long as you give appropriate credit and provide a link/reference to this page.

That is it. You don't need our permission to copy the article; just include a link/reference back to this page. You can use it freely (with some kind of link), and we're also okay with people reprinting in publications like books, blogs, newsletters, course-material, papers, wikipedia and presentations (with clear attribution).

This article is a part of the guide:

Browse Full Outline

- 1History of the Scientific Method

- 2Who Invented the Scientific Method?

- 3Before the Greeks

- 4Mesopotamia

- 5Greek Science

- 6Building Roman Roads

- 7Islamic Science

- 8Middle-Ages Science

Footer bottom