Jorge Cham, creator of phdcomics.com tells us about the Science Gap at TEDx, UCLA.

Speaker: Jorge Cham, creator of the online comic strip "Piled Higher and Deeper (PHD)"

Venue: September 20, 2012, TEDx, UCLA.

I'm a cartoonist, as Scott mentioned. To me, cartooning is about taking a blank page and filling it with your ideas. The idea that I want to draw out for you guys here today is this idea of the science gap. I'm a cartoonist, but in addition to that, I also have a PhD in robotics.

You might be wondering, what does cartooning and robotics have in common? What do they have to do with each other? I can tell you that my parents are also very concerned about that.

Because of this kind of unique combination of academia and the arts, I find myself a lot of the time traveling all over the world talking to scientists and researchers about what they do and how they do it. It's very interesting to me to learn all the things that we know about the universe, about our bodies, about ourselves, and about our societies, but even more interesting, more amazing to me, is to find out how much we don't know.

For example, here are some things that you'd think that we as a human species would know by now but actually don't, starting with first of all, what is 95 percent of the universe made out of?

Ninety-five percent right? All those billions of stars, all the atoms in this room, inside of me, inside of you. That's just five percent of the entire universe. What's the other 95 percent? We don't actually know, apparently.

Even the stuff that we think we know about, the five percent, there are still so many questions that we don't know, like what id cancer, how do we cure it, what is gravity, what makes markets work, what is Alzheimer's disease, how do we cure it, and on and on and on. There are so many questions that we still don't know.

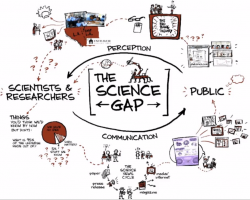

That's not actually the gap that I want to talk to you about here today. The gap that I do want to talk to you about today is this gap between the people who are trying to come up with answers to these questions and the general public. Right now, if you're a scientist or a researcher, the main way that you have for communicating what you do to the public basically is these following things have to happen.

First of all, you have to write a long and esoteric journal paper, and then your university may be able to issue out a press release about it. Then maybe some reporter somewhere will actually catch this press release, and maybe they'll get interested about it, and maybe they'll talk to their editor about it, and then maybe they'll write a good story about it, and maybe they'll do a good job of it. And then maybe they'll actually get published somewhere. But it won't actually reach the public really unless the general media picks it up or the internet picks it up. Then maybe it'll actually reach the public, and then maybe somebody will actually read it and understand it.

That seems a little bit suboptimal to me, but then something pretty interesting happened to me last year. I was contacted by this physicist called Daniel Whiteson from UC Irvine. I know you're UCLA, but you shouldn't laugh at UC Irvine just because I said UC Irvine.

He contacted me, and he said, "Jorge, I want to pay you to write a comic about the Higg's boson."

I said, "What?"

He's like, "Yeah, I feel like people are really curious about this topic, and the media's not doing a very good job of explaining what it is."

I said, "Sure." I went and I interviewed him, and I recorded this conversation that I had with him. At the same time, I was looking on the internet. People were really experimenting with YouTube videos and taking recordings and making animations of it.

I decided to also experiment, and so we made this video about this animation that explains what the Higg's boson is that when the Higg's boson was discovered, or some form of it was discovered earlier this year, this video went viral. It was everywhere. It was posted in all kinds of media outlets and websites. Millions of people saw this video, and they understood a little bit more about what these scientists were trying to do.

Imagine that, the best and most clear explanation of what this complex and nuanced topic was came from a scientist himself in his own voice who took the initiative to hire a cartoonist and experiment with new ways to close this gap between him and the public. He didn't wait around for the press release, he didn't wait around for the reporter to come calling, he just took the initiative and did it.

That's pretty cool, but I think part of the general problem is also that there's another gap I think between scientists and the public, which is in how the public perceives scientists and researchers. I know this because probably the thing I'm most known for as a cartoonist with a PhD, as you know, the most overeducated cartoonist in the history of mankind.

The thing I'm probably most known for is to make this comic strip called Piled Higher and Deeper, or PhD Comics. This is a comic strip that I started while I was in grad school because you have a lot of free time in grad school.

People sometimes call it the Dilbert of academia, or they say that it's really interesting because it actually portrays scientists in academics as real people. Apparently, they're not robots. I'm an expert, so I think I would know the difference.

These comic strips, they're pretty popular in academia. They get forwarded around a lot. The website gets about seven million visitors a year, but outside of academia and the general public, most people haven't heard about it.

What they have probably heard about is probably one of the most popular television sitcoms in network TV today. It's a show called The Big Bang Theory.

Exactly. Some people groan, some people cheer. The Big Bang Theory is a major TV network show that's also supposed to be at scientists and researchers. The show has a lot of fans, and I don't want to offend them, especially on the internet.

The show does show smart people as these . . . All the smart people in the show, they have their glasses, they dress really weird, they're socially inept. And all the pretty, cool people, they're blonde, they're dumb, they're outgoing, and et cetera. I don't have anything personal against this show, but I do worry about what impact these stereotypes have on society in general.

For example, I sometimes volunteer in this middle school in East LA called Endeavor College Prep. These are kids that come from very disadvantaged communities. Most of them, their parents never went to college. Half of them statistically won't even graduate from high school.

For all we know, the next Einstein or the next Marie Curie or the next Darwin could be sitting in one of those classrooms now. I wonder sometimes what these stereotypes, the effect that they have.

First of all, how are these kids going to get communicated the science that they need to catch up and become these superstars, but most importantly, how are they going to ever see themselves as future scientists or researchers if all they see when they turn on the TV are these stereotypes and caricatures of what scientists and researchers are supposed to be?

My point here today is that what we don't know about the universe should inspire us, but should also inspire us to try to close these gaps in communication and in perception so that more people, most of us, most of the human species, can participate and be engaged in looking for these answers so that maybe we can even discover new blank pages to fill up with ideas. So, thank you.